Summary

In 1924, Congress regularized the U.S. citizenship status of all Native Americans by birthright. All other persons born within the United States had gained citizenship with the Fourteenth Amendment but not Native Americans, whose citizenship status had been allocated irregularly depending on descent, gender and marital status, and status to their tribal nations.

Source

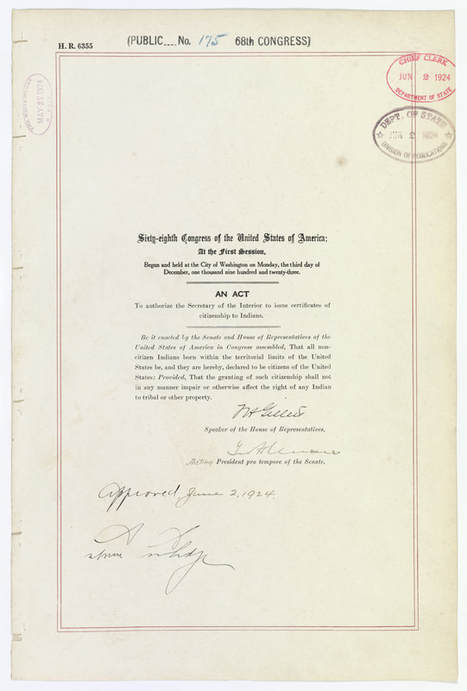

BE IT ENACTED by the Senate and house of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That all non citizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States be, and they are hereby, declared to be citizens of the United States: Provided That the granting of such citizenship shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to tribal or other property.

Approved June 2, 1924

Analysis

The SAI (Society of American Indians) has been criticized for desiring a US citizenship that would render Native sovereignties obsolete, based on the dichotomies conceived at the time: that “achieving” U.S. citizenship meant refusing tribal authority. The settler-colonial concept of citizenship . . . made the mutual exclusivity of Indian “ward” and US “citizen” appear inescapable and natural. At the time ward versus citizen looked like the only choice possible . . . .

Faced with the choice between Indian wardship’s bitter subjugations and US citizenship’s illusory freedoms, the SAI chose citizenship. Perhaps they chose the possibilities they could imagine within citizenship and a plural democratic nation. In their work for Native people, SAI intellectuals developed layered possibilities that stretched far beyond the false dichotomy of savagery versus civilization posed by settler colonial society. Local work imagined and opened up possibilities of living as fully modern citizens, dynamic contributors to the democratic life of the US, and as nations with inherent sovereignty. In the past century Native individuals, nations, and intellectuals have further developed ideas of multiple, layered citizenships and multiple, layered sovereignties that open up possibilities rather than block them off. Native peoples must have the power to make choices within the realm of possibilities, not the realm of foreclosed opportunities.

Excerpt from:

Lomawaima, K. T. (2013). The mutuality of citizenship and sovereignty: The Society of American Indians and the battle to inherit America. American Indian Quarterly, 37(3), 333-351.