Summary

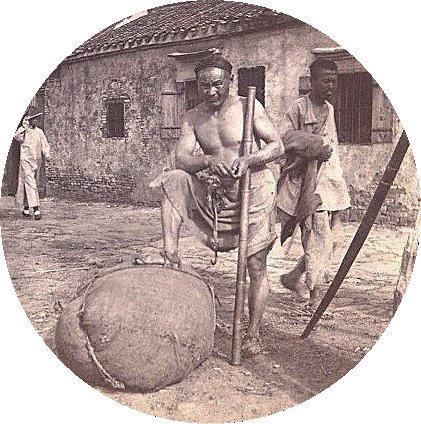

During the Civil War, the Republican Congress sought to prevent southern plantation owners from replacing their enslaved African American workers with unfree contract or “coolie” laborers from China. Southern landowners, anticipating the demise of slavery, began recruiting “coolie” workers–indentured and exploited workers generally from China or India–common on plantations in the Caribbean. Chinese workers seemed an ideal replacement workforce for slaves because the planters believed them to be a racially distinct, cheap, and controllable labor force. In reality, many Chinese workers simply signed contracts to pay for fixed costs of passage that they paid off by working for set terms after arrival and were not slave-like “coolies” without free will and independence. This conflation of Chinese contract workers with African slaves and unfree “coolies” later fueled anti-Chinese immigration campaigns. This law was not actively enforced because it was impossible to systematically identify “coolies.”

Source

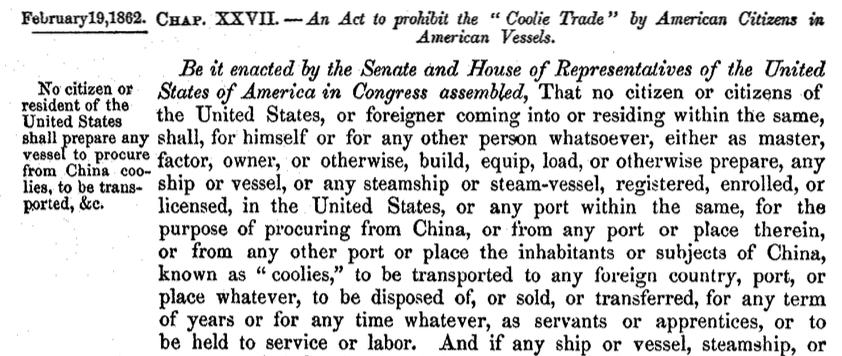

CHAP. XXVII. – An Act to prohibit the ” Coolie Trade” by American Citizens in American Vessels.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives . . . That no citizen or citizens of United States, or foreigner coming into or residing within the same, shall . . . vessel to procure factor, owner, or otherwise, build, equip, load, or otherwise prepare, any steamship for the purpose of procuring from China . . . the inhabitants or subjects of China, known as “coolies” . . . to be disposed of, or sold, or transferred, for any term of years or for any time whatever, as servants or apprentices, or to be held to service or labor. And if any ship or vessel . . . belonging in whole or in part to citizens of the United States . . . shall be employed for the said purposes, or in the “coolie trade,” so called, or shall be caused to procure or carry from China . . . any subjects of the Government of China for the purpose of transporting or disposing of them as aforesaid, every such ship or vessel . . . shall be forfeited to the United States, and shall be liable to be seized, prosecuted, and condemned . . . .

SEC. 3. And be it further enacted, That if any citizen or citizens of on board a vessel the United States shall . . . take on board of any vessel, or receive or transport any such persons as are above described in this act, for the purpose of disposing of them as aforesaid, he or they shall be liable to be indicted therefor, and, on conviction thereof, shall be liable to a fine not exceeding two thousand dollars and be imprisoned not exceeding one year . . . .

SEC. 4. And be it further enacted, That nothing in this act hereinbefore contained shall be deemed or construed to apply to or affect any free and voluntary emigration of any Chinese subject, or to any vessel carrying such person as passenger on board . . . .

SEC. 6. And be it further enacted, That the President of the United States shall be, and he is hereby, authorized and empowered . . . to direct and order the vessels of the United States, and the masters and commanders thereof, to examine all vessels navigated or owned in whole or in part by citizens of the United States . . . whenever, in the judgment of such master or commanding officer thereof, reasonable cause shall exist to believe that such vessel has on board, in violation of the provisions of this act, any subjects of China known as “coolies,” for the purpose of transportation . . . .

Analysis

“The legal exclusion of Chinese laborers in 1882 and the subsequent barrage of anti-Asian laws reflected and exploited this consensus in American culture and politics: “coolies” fell outside the legitimate borders of the United States . . . . A year before Abraham Lincoln delivered the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, he emblematized this consensus by signing into law a bill designed to divorce “coolies” from America, a little known legislation that reveals the complex origins of U.S. immigration restrictions. While marking the origination of the modern immigration system, Chinese exclusion also signified the culmination of preceding debates over the slave trade and slavery, debates that had turned the attention of proslavery and antislavery Americans not only to Africa and the U.S. South but also to Asia and the Caribbean.”

Moon-Ho Jung, “Outlawing “Coolies”: Race, Nation, and Empire in the Age of Emancipation,” American Quarterly 57, No. 3 (Sep., 2005): 678.