Asian Immigration

Summary

For most of U.S. history, Asian immigrants have been defined as racially ineligible for citizenship (1790-1952) and therefore subject to the most severe immigration restrictions. Stereotyped as a “yellow peril” invasion consisting of slavish “coolie” labor competition, Chinese were the earliest targets for actively enforced immigration controls through the Chinese Exclusion Laws (1882-1943), followed by Japanese and the Gentlemen’s Agreement (1907-1908), persons from a zone extending from the Middle East to Southeast Asia (Barred Zone Act, 1917), and Filipinos from the U.S. colony (Tydings McDuffie Act, 1934). As the earliest targets for exclusion, anti-Asian laws and their enforcement provided the foundations of legal ideologies and enforcement practices for the more general immigration restrictions that later followed. The lesser protections and legal status of noncitizens and excludable aliens were developed in relation to Asian immigrants, including the rationale of “military necessity” that was used to justify incarceration of about 120,000 Japanese Americans, two-thirds of whom were U.S.-born citizens, in detention camps during World War II as racially categorized “enemy aliens.”

Asian immigration remained at a trickle until immigration laws were reformed. World War II, the growing unacceptability of open racial discrimination, and greater concerns for international relations led to the gradual removal of overtly anti-Asian immigration laws which were eventually replaced in 1965 with preferences for skilled employment, family unification, and refugees. These changes led Asian immigration to increase at geometric rates and come from more diverse origins. Asians now disproportionately immigrate through the skilled employment preferences which have fed new stereotypes of Asians as “model minorities” whose high levels of educational and economic attainment suggest that racism has disappeared in U.S. society. [graph of immigration, 1821-2000] The reality is more complicated because many Asians are able to immigrate only because they are already highly educated or wealthy.

Read More

Asians journeyed primarily across the Pacific in reaching a United States that had been founded by transatlantic travelers from Europe. Asians thus confounded the narrative of westward expansion and migration that is widely understood to be a defining characteristic of the developing United States. As racial minorities presumed to hold starkly different modes of civilization and cultural values, Asians became ready targets for the earliest systematically enforced immigration restrictions and exclusions from citizenship.

Chinese were the first to arrive in significant numbers, drawn by the gold rush but also by the burgeoning economic opportunities of the newly established state of California in the form of trade, commercial agriculture, domestic services, a variety of light manufacturing industries, and infrastructural projects such as railroads, dikes, and land reclamation. Congress had already determined that Asians were “aliens ineligible for citizenship” by passing the 1790 Nationality Act which permitted only “free white persons”–in practice, white male property owners—to gain citizenship through the legal process of naturalization. Mexicans had gained citizenship rights with the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo by which the United States annexed northern Mexico and granted citizenship to Mexican residents while African Americans formally gained citizenship with the Fourteenth Amendment passed in 1868. Asian immigrants, however, remained “aliens ineligible for citizenship” until 1952.

Barred from citizenship and already stereotyped as irrevocably foreign and inferior even as Darwin’s theories of evolution and “survival of the fittest” seemed to vindicate beliefs in racial differences, Asians made ready targets for early attempts at immigration restriction. Congress began with limited regulations that banned the entry of Chinese as coolies, contract laborers, and prostitutes. During the 1870s, pressures mounted for more extensive laws with the nation riven by economic contractions, unemployment and labor unrest, and increasing immigration. By 1876, both major political parties courted the swing state California’s electoral votes, which required an anti-Chinese platform. Even so, what came to be known as Chinese exclusion took six more years to legislate after some jousting between the White House and Congress about how to enact laws that singled out Chinese without offending the Chinese government and renegotiation of the 1868 Burlingame Treaty which had previously secured rights of free migration by Chinese and Americans in order to maintain the access of U.S. employers to Chinese workers. Passed in 1882, “An Act to execute certain treaty stipulations relating to Chinese” chiefly targeted Chinese laborers and identified Chinese by race as barred from entering the United States apart from six exempt classes: merchants, merchant family members, diplomats, tourists, students, and returning laborers. Through efforts to enforce this law targeting Chinese, the federal government defined its sovereign and plenary powers over immigration, the agencies charged with carrying out these goals, and limited legal protections and status for unauthorized immigrants, or excludable aliens, who were subject to being rounded up, detained, and deported.

Chinese evasions and manipulations of U.S. immigration law, primarily by crossing both the northern and southern land borders and fraudulent identity claims, led federal authorities to assert expanding powers over excludable aliens. The 1888 Scott Act abolished legal entry for returning laborers, an exempt category subject to high levels of fraud. The 1892 Geary Act extended the Chinese Exclusion Law for ten more years and required Chinese in the United States to carry a Certificate of Residence to verify legal entry or face detention and deportation. Chinese challenged each reduction in their legal status and protections in court, citing the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantees of equal protections and due process but the Supreme Court ruled that in matters pertaining to immigration, the U.S. federal government held “sovereign and plenary powers.” Present-day vulnerability of unauthorized immigrants to detention and deportation trace back to these laws and court cases concerning Chinese in the 1880s and 1890s. The only right secured by Chinese immigrants came with the 1898 Wong Kim Ark Supreme Court case, which established the Fourteenth Amendment principle that any person born in the United States, regardless of race or parents’ status, held U.S. citizenship by birth. This landmark case still stands as the primary means available to unauthorized immigrants to gain a permanent toehold in this country.

As numbers of Chinese immigrants diminished, Japanese arrived in greater numbers recruited to replace them in agricultural labor on the west coast and Hawaii, domestic service, lumberyards, and on railroads. Continued violence and agitations by California’s Anti-Asiatic League led President Theodore Roosevelt to broker a diplomatic arrangement, the Gentlemen’s Agreement, with the Japanese government whereby Japan self-restricted the emigration of Japanese laborers to the U.S. to avoid the humiliation of being barred from entry. Other Asian countries received less consideration, as the 1917 Immigration Act summarily banned from entry persons originating from the so-called “Barred Zone” which extended from the Middle East to Southeast Asia from which no persons were allowed to enter the United States.

During the 1920s, the United States continued to harden its line against immigrants with the Supreme Court affirming in the 1922 Ozawa v. U.S. and 1923 Thind v. U.S. cases that Asian immigrants were racially ineligible for citizenship, regardless of high levels of acculturation and the classification of Indians as Aryans, or white. The 1924 Immigration Act banned altogether immigration by all “aliens ineligible for citizenship,” thereby greatly offending the Japanese government, and imposed an inegalitarian system of national origins quotas that shrank European immigration several fold, thereby making clear that the United States welcomed chiefly immigrants from northern and western Europe. National origins quotas remained the main principle of immigration restriction until 1965. Despite coming from a U.S. territory, Filipinos also became subject to immigration restriction with the 1934 Tydings-McDuffie Act, which granted the Philippines eventual independence and an annual immigration quota of only 50.

The racialization and treatment of Asians as inassimilable foreigners reached extremes during World War II with the mass incarceration of about 130,00 Japanese Americans, two-thirds of whom were U.S.-born citizens. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese Americans were categorized racially as “enemy aliens.” As suspects for potential espionage and treason, even though no evidence was ever uncovered, Japanese Americans became subject to the principle of “military necessity” and placed under curfew orders before being rounded up and confined in incarceration camps away from the coast. Court challenges such as Korematsu v. U.S. upheld the principle of military necessity for such treatment and still stands to this day. The case of ex parte Endo, which was not decided until December 1944, paved the way for the release of those Japanese American citizens whom the U.S. government found to be “concededly loyal.” Japanese immigrants, who could not legally naturalize however, were still aliens and confined in the camps until the war’s end.

Even as the United States imposed its most draconian system of immigration restriction, international students constituted a welcomed and growing form of circulatory migration. Educated elites, intellectuals, and potential political leaders from China, Japan, the Philippines, India, and Korea gained entry to some of the most elite universities and colleges in the United States, often with the active support of the U.S. government and other Americans sympathetic to elite Asians who might wield influence friendly to the United States in their home countries.

These kinds of considerations fostered the rollback of Asian exclusion. World War II followed by the Cold War applied tremendous pressures to fortify alliances with key partners in Asia, regardless of racial differences. With the 1943 Repeal of Exclusion, Chinese became the first Asians to gain naturalization rights and also a small immigration quota of 105. Other Asian allies, Indians and Filipinos followed suit in 1946 through the Luce-Celler Act. Through immigration restriction and limited opportunities, the population of Asians had remained at low levels that presented few problems domestically, especially in comparison to much larger populations of African and Mexican Americans. Congress realized that it need not enact offensive outright exclusions of racialized groups, but could impose low numeric limits on their legal immigration. The 1952 McCarran-Walter Act implemented this version of limited reform by retaining the national origins quotas, providing quotas to all countries, but some with very low quotas. Japan had the highest Asian quota at 185. Even as Asians remained the only group tracked by race through the Asian-Pacific Triangle, which capped overall immigration at 2,000 per year, they finally gained naturalization rights with the abolishing of racial restrictions. The 1952 Act made provisions for the Attorney General to admit refugees on a parole basis and for the first time implemented a preference system that favored “skilled” or knowledge workers and family reunification.

These new priorities for immigration admission enabled several tens of thousands of Asians to immigrate as refugees, albeit through piecemeal refugee legislation. Growing numbers of international students legally found employment after receiving their graduate degrees and pathways to legal permanent residency and citizenship. By the mid-1960s, the phenomenon of educated elites from developing economies immigrating to the United States became known as “brain drain,” and was chiefly associated with highly educated Asians in technical fields.

In the aftermath of World War II, racial barriers targeting Asians began crumbling earlier than for other minority populations of color. Legislation for the admission of military spouses and fiancées sanctioned mixed race families a couple of decades before the Supreme Court banned antimiscegenation laws with Loving v. Virginia (1967), as did practices of transnational, transracial adoptions that became acceptable starting with the Korean War. Asian Americans gained access to mainstream employment sectors, particularly through educational credentials, thereby gaining the image of “model minorities.” This new stereotype drew on the increasing visibility of Asians on university and college campuses and employed in professional and technical fields while ignoring the reality that many Asians gained entry to the United States through higher education and employment preferences in immigration laws.

The 1965 Immigration Act solidified these demographic changes by providing three main pathways to legal immigration through an expanded system of preferences that allocated 75 percent of immigrant visas for family reunification, 20 percent for employment, and 5 percent for refugees. [Pathways to legal immigration since 1965] Although its proponents believed the emphasis on family reunification would preserve the predominance of European immigrants at a time when 85 percent of the U.S. population was white, those most motivated by economic and political instability to immigrate came from poor and politically unstable nations in Asia and elsewhere in the developing world. Each country in the eastern hemisphere received a uniform cap of 20,000 immigrant visas per year. Of these, disproportionate numbers of Asians immigrate through the employment preferences and must be processed by an employer and certified by the Department of Labor. These systems favor the highly educated employed in fields designated as needed in the United States, chiefly in the sciences and technology. [Most common immigrant jobs by state, 2015]

The Asian American population of the United States has increased at geometric rates and now includes over 40 different nationality groups who arrive initially through employment preferences or as refugees, which then opens the door to more immigration through family reunification. Refugee admissions after the Vietnam War contribute to this diversity and have produced almost entirely new communities of Southeast Asians who struggle more for socioeconomic integration and educational attainment because most arrive without such credentials. In aggregate, the Asian American population is about 70 percent foreign-born, with attributes closely shaped by immigration regulations.

The Immigration Act of 1990 has further exacerbated “model minority” characteristics by enacting the H-1B visa program that grants temporary work visas for “skilled workers” but can provide a pathway to citizenship with the cooperation of employers. A majority of recipients work in the computer industry and come from Asia, particularly India and China. Because their numbers before 1965 were so low, and the growth in their population by immigration has been so steep, Indian Americans exhibit the highest statistical adherence to the model minority attributes in the form of household incomes, percentages of college graduates and those holding graduate degrees, but also rates of foreign-born.

The “model minority” stereotype operates so powerfully that when Asians became the fastest growing immigrant group in America for the first time in 2009, overtaking Latinos who had held the lead since the 1950s, little public outcry or alarm ensued. The economic downturn contributed to this shift. Nonetheless, compared to the 1870s when but a trickle of Asian migration produced the onslaught of fear and racial anxieties that produced Asian exclusion, contemporary acceptance of Asian immigrants reveals how effectively U.S. immigration policies and institutions have limited their immigration in ways that satisfy general values concerning economic competitiveness and national security. Immigration laws and bureaucracy are now effective enough in maintaining Asian immigration at acceptable levels that primarily admit those seen as bearing sufficient economic or political advantages to justify their admission and settlement. Immigration as model minorities, despite its comparative advantages, nonetheless burdens Asian Americans with the necessity of achieving beyond national averages in order to gain admission and acceptance in the United States.

Lesson Plan

Introduction

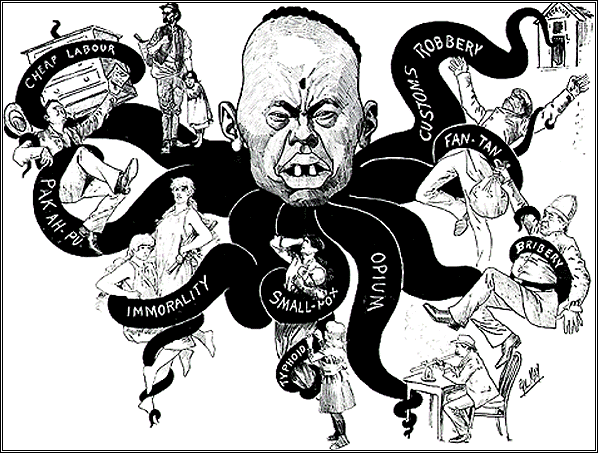

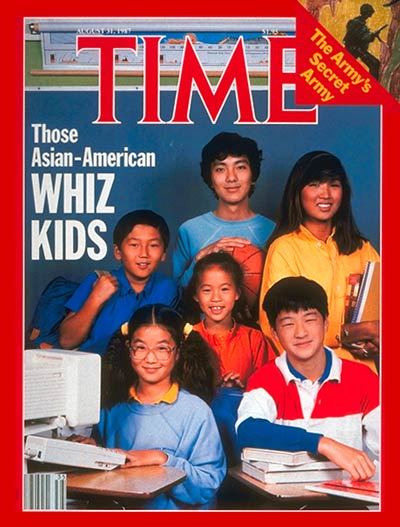

1) Have students compare Sources A and B considering the question, how are Asians/Asian Americans characterized in each image? Change and continuity are both factors.

Source A:

Source B

2) Ask students why they think images of Asians and Asian Americans shifted from 1886 (date of source A) to 1987 (date of Source B).

Transition:

Immigration history, while reflecting the socio-political and economic context of each policy and law, continues to shape present communities.

Guided Activities:

1) Divide students into groups and assign each group a chart or charts. Have them develop general statements based on the assigned H-1B trend tables (h-1b-2007-2017-trend-tables).

(e.g. what is the country/continent of origin for most individuals who are allowed into the U.S. through an H-1B visa? What is the general education level of applicants/approved individuals? etc.).

-General Info about H-1B Visas

The H-1B Program

The H-1B program allows companies in the United States to temporarily employ foreign workers in occupations that require the theoretical and practical application of a body of highly specialized knowledge and a bachelor’s degree or higher in the specific specialty, or its equivalent. H-1B specialty occupations may include fields such as science, engineering and information technology (from USCIS).

2) Have students write out their statements from the trend tables so that the entire class can see each statement.

3) Ask students what connections might be made between the statements and Source B.

4) The Washington Post offers a ~5 minute video explaining the model minority myth.

5) Looking at the myth through immigration history: Assign to half the student groups, one immigration policies/laws (pre-1943) related to Asian migration and have groups prepare a post-it with a sentence that explains why Asians were excluded from immigration/citizenship according to the law.

-Assign to the other half of the student groups, one immigration policy/law related to the inclusion of Asians to immigration flows/citizenship (starting with 1943). Have each group prepare one post-it with a sentence that explains how Asians were included into immigration/citizenship.

-When groups finish, they will put their post-its into a timeline. As a class (or have already prepared), label key events and eras (e.g. the Great Depression, the Cold War, WWII, the gold rush, etc.)

-Model a connection between a key event and a key policy. For example, how the repeal of Chinese Exclusion (1943) is related to WWII allies. In groups, have students discuss other possible connections.

6) Written assessment/Class discussion: Beyond controlling migration flows into the U.S., what are other ways immigration laws and policies can become tools that impact the country?

Chronology

This was the first law to define eligibility for citizenship by naturalization and establish standards and procedures by which immigrants became US citizens. In this early version, Congress limited this important right to “free white persons.”

This California Supreme Court case ruled that the testimony of a Chinese man who witnessed a murder by a white man was inadmissible, denying Chinese alongside Native and African Americans the status to testify in courts against whites.

During the Civil War, the Republican-controlled Congress sought to prevent southern plantation owners from replacing their enslaved African American workers with unfree contract or "coolie" laborers from China.

Ratified in 1868 to secure equal treatment for African Americans after the Civil War, the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed birthright citizenship for all persons born in the United States. It also provided for equal protections and due process for all legal residents.

The Naturalization Act of 1870 explicitly extended naturalization rights already enjoyed by white immigrants to “aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent,” thus denying access to the rights and protections of citizenship to other nonwhite immigrant groups.

This program sent about 120 Chinese students to study in New England and is often cited as a pioneering effort in mutually beneficial systems of international education which promoted the sharing of knowledge and understanding and improved international relations.

This Supreme Court decision affirmed that the federal government holds sole authority to regulate immigration.

This treaty updated the 1868 Burlingame Treaty with China, allowing the United Stated to restrict the migration of certain categories of Chinese workers. It moved U.S. immigration policy closer to outright Chinese exclusion.

This law was a major shift in U.S. immigration policy toward growing restrictiveness. The law targeted Chinese immigrants for restriction-- the first such group identified by race and class for severely limited legal entry and ineligibility for citizenship.

Congress extended domestic authority over immigration to improve enforcement of the Chinese exclusion laws. It abolished one of the exempt statuses, returning laborers, stranding about 20,000 Chinese holding Certificates of Return outside the United States.

This Supreme Court decision affirmed the plenary powers of U.S. federal authorities over immigration matters, in this instance even when changes in U.S. immigration law reversed earlier policy and practice.

This Supreme Court decision ruled as constitutional the 1892 Geary Act's requirement that Chinese residents, and only Chinese residents, carry Certificates of Residence to prove their legal entry to the United States, or be subject to detention and deportation.

Increasing immigration, mainly from southern and eastern European countries, along with a series of economic downturns fueled nativist fears and the founding of the Immigration Restriction League by three influential Harvard graduates.

This Supreme Court decision that detention by immigration authorities does not constitute a criminal punishment, affirming the lesser rights of excludable aliens.

This Supreme Court case established the precedent that any person born in the United States is a citizen by birth regardless of race or parents' status.

Congress extended the Chinese exclusion laws in perpetuity in response to the Chinese government's efforts to leverage better conditions for Chinese travelers to the United States by abrogating earlier treaties. Chinese communities organized an anti-American boycott in protest.

An international coalition of Chinese merchants and students coordinated boycotts of U.S. goods and services in China and some cities in Southeast Asia to protest the Chinese Exclusion laws.

Rather than enacting racially discriminatory and offensive immigration laws, President Theodore Roosevelt sought to avoid offending the rising world power of Japan through this negotiated agreement by which the Japanese government limited the immigration of its own citizens.

California, along with many other western states, enacted laws that banned "aliens ineligible for citizenship" from owning or leasing land. The Supreme Court upheld these laws as constitutional.

Although this law is best known for its creation of a “barred zone” extending from the Middle East to Southeast Asia from which no persons were allowed to enter the United States, its main restriction consisted of a literacy test intended to reduce European immigration.

The hardening of U.S. isolationism set the stage for the Supreme Court to affirm the 1790 Nationality Act's stipulation that Asians are ineligible for naturalization because they are racially not "white" regardless of their demonstrated acculturation and integration.

Contradicting the logic behind its ruling in Ozawa v. U.S., the Supreme Court found that Bhagat Singh Thind was also ineligible for citizenship even though as an Asian Indian, who were as caucasians, he was racially white.

To further limit immigration, this law established extended "national origins" quotas, a highly restrictive and quantitatively discriminatory system. The quota system would remain the primary means of determining immigrants' admissibility to the United States until 1965.

Completing the racial exclusion of Asians, Congress imposed immigration restrictions on Filipinos by granting the Philippines eventual independence. Previously, Filipinos could immigrate freely as U.S. nationals from a colony of the United States.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed this war-time executive order authorizing the rounding up and incarceration of Japanese Americans living within 100 miles of the west coast.

The importance of China as the U.S. government's chief ally in the Pacific war against Japan led Congress to repeal the Chinese Exclusion laws, placing China under the same immigration restrictions as European countries.

In December 1944, the Supreme Court authorized the end of Japanese American incarceration by ruling that "concededly loyal" U.S. citizens could not be held, regardless of the principle of "military necessity."

Congress enacted exceptions to the national origins quotas imposed by the Immigration Act of 1924 in order to help World War II soldiers and veterans bring back foreign spouses and fiances they had met while serving in the military.

This law further undermined Asian exclusion by extending naturalization rights and immigration quotas to Filipinos and Indians as wartime allies.

In contrast lawmakers' widespread indifference before World War II, after the war, under pressure from the White House and Department of State, Congress authorized admissions for refugees from Europe and permitted asylum seekers already in the U.S. to regularize their status.

The McCarran-Walter Act reformed some of the obvious discriminatory provisions in immigration law. While the law provided quotas for all nations and ended racial restrictions on citizenship, it expanded immigration enforcement and retained offensive national origins quotas.

Dissatisfaction with the 1952 McCarran-Walter Act inspired support for this legislation which provided 214,000 visas to refugees, primarily from Europe but with 5,000 designated for the Far East.

The Immigration Bureau and the FBI used this program to try regularize the statuses of the many Chinese Americans who had entered the United States using some form of immigration fraud under the discriminatory Chinese exclusion laws.

This law added more exceptions to immigration restriction by national quotas by categorizing international adoption as a form of family reunification.

This law opened the door to immigration by highly skilled workers from countries with low immigration quotas, anticipating the Immigration Act of 1965's emphasis on employment preferences.

This law set the main principles for immigration regulation still enforced today. It applied a system of preferences for family reunification (75 percent), employment (20 percent), and refugees (5 percent) and for the first time capped immigration from the within Americas.

The UNHCR issued this protocol in 1967 to implement the goals of the 1951 Refugee Convention, which set forth the key principle of refoulement, or that persons in flight from persecution and danger cannot be forced to return to places of danger.

The United States made provisions to admit about 135,000 Vietnamese and other Southeast Asians in the months following the fall of Saigon, resettle them across the United States with resources to help them establish new lives.

The courts vacated the 1944 Supreme Court conviction of Fred Korematsu for violating curfew orders imposed on Japanese Americans after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Congress revised the Immigration Act of 1965 by implementing the H-1B visa program for skilled temporary workers, with some provisions for conversion to permanent status, and the diversity visa lottery for populations unable to enter through the preference system.

Legislated in response to the brutal Chinese government crackdowns on student protests in Tiananmen in 1989, this law permitted Chinese students living in the United States to gain legal permanent status.

Trying to cope with the long-term residence of millions of unauthorized immigrants, this executive order provided protection from deportation and work authorization to persons who arrived as minor children and had lived in the United States since June 15, 2007.

This executive order issued by the Obama White House sought to defer deportation and some other protections for unauthorized immigrants whose children were either American citizens or lawful permanent residents.