Immigration and International Relations

Summary

International relations act as a constraint and major priority in immigration policies. Key relationships between countries are based on the circulation of people for purposes such as diplomacy, business and trade, education, research, tourism, and other forms of cooperation and mutual understanding in addition to immigration. Imposing bans and restrictions on immigration can be construed as national insults, especially when applied unequally, that may damage matters such as trade relations and how Americans are treated abroad. Thus the earliest restrictions, which singled out Chinese and then Japanese by race, involved diplomatic negotiations which secured agreement from the governments of the targeted countries to these discriminations, signalling that international standards for immigration regulation were in the process of being worked out. Until 1965, the United States avoided imposing restrictions within the western hemisphere to maintain friendly relations with its closest neighbors and to maintain access to nearby workers. Its imposition of the strictest immigration laws in the 1920s, through a system of unequal national origins quotas, displayed national isolationism that persisted until World War II. The compelling international crisis forced the United States to vehemently rejoin world politics, in part by reforming immigration laws which it now sought to use to strengthen relations with politically allied countries around the world. During the Cold War, these shifting priorities made restrictions based on race and national origins unacceptable, while raising pressures to admit refugees. The 1965 Immigration Act implemented these goals, by placing all countries on the same basis for immigration restriction by emphasizing family reunification, economic priorities, and refugees and giving all countries the same annual quota. This surface uniformity has generated considerable problems, however, because patterns of migration between the United States and its nearest neighbors in the western hemisphere are significantly greater and more complex than those with more distant countries. The problem of the sizable population of unauthorized immigrants long-resident in the United States, most of whom come from the Americas, requires Congressional action to resolve in ways that protect U.S. relations with its neighbors.

Read More

International relations are a major but often overlooked aspect of immigration policies which are responsible for maintaining convenient traveling conditions for migrants whose travels improve relationships between allied countries. These kinds of lawful migrations include journeys for legal immigration, diplomacy, business and commerce, education, research, sharing of technology and expertise, tourism, and many other kinds of exchanges for matters such as culture and athletics. The majority of persons affected by immigration policy are those who regularly circulate for such collaborative purposes even though most public awareness and resources are directed to identifying and managing restricted categories of persons. Restrictions against excluded persons attract so much attention and generate so much conflict because targets for exclusion are fraught subjects. Selectively banning or limiting migration may be seen as insults to other countries or as targeting certain populations in ways that signal national disdain and even outright hostility with damaging effects on international relationships and possibly how Americans are treated abroad.

Political threats were the targets of the United States’ earliest immigration restrictions. These laws responded to specific circumstances and were not systematically enforced. The 1798 Alien and Sedition Acts sought to limit migrants in anticipation of a war with France and made citizenship by naturalization more difficult to obtain. An 1803 ban on entry by “negroes” targeted participants in the Haitian Revolution in fears that they would spread anti-slavery campaigns. During the twentieth century, barring entry to proponents of unwelcome political beliefs led Congress to restrict anarchists (1903) and radicals (1918) by legalizing measures to round up and expel targeted activists in the Palmer Raids. The Cold War identified leftists and communists as threats to national security and added provisions for their detention and removal in the 1952 McCarran-Walter Act. In the twenty-first century, in the wake of 9-11, the United States has enacted measures to track and restrict potential terrorists and the use of airplanes as weapons of mass destruction.

The next intersection of foreign relations and immigration and citizenship policy arose with the many foreign populations that became part of the United States through conquest and colonization. Their statuses were also handled through treaty negotiations. Such processes began with the claiming of indigenous lands starting with the thirteen colonies and continuing throughout the United States’ westward expansion toward the Pacific. Legally, Native Americans were considered citizens of their sovereign tribal nations, not of the United States, through a complicated system of treaties and the reservation lands on which they lived. Not until 1924 did Native American peoples uniformly receive rights of U.S. citizenship by birth. Mexicans also became part of the United States through the U.S.-Mexican War and the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Those choosing to remain resident gained citizenship automatically. When the United States claimed overseas territories in 1898, the new colonial subjects received varying legal statuses. That year, the United States formally annexed Hawaii and acquired Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines after the Spanish American War. Hawaiians and Puerto Ricans gained citizenship and Cubans eventually gained their independence. In contrast, the Philippines became an unincorporated U.S. colony so that Filipinos were considered U.S. nationals with rights only to travel to the United States, but not gain citizenship. Continuing Filipino migrations within the U.S. empire aggravated anti-Asian tensions during the 1920s and 1930s because it continued after the exclusion of all other Asians. West coast agitations against Filipinos led Congress to enact the 1934 Tydings-McDuffie Act, which granted the Philippines eventual independence so that Filipino immigration could be restricted.

When the United States began actively trying to limit immigration, it did so by race and nationality with the U.S. government taking the precaution of first diplomatically negotiating its rights to restrict immigration with the targeted countries. Chinese (1882)* and then Japanese (1907-08)* were the earliest targets of U.S. restrictions because they were seen as obviously unsuitable immigrants who were racially distinct, inferior, and therefore unassimilable. Even so, the United States enacted restrictions only after receiving concurrence from the Chinese and Japanese governments. The international nature of immigration restriction is also illustrated by the Customs Bureau serving as the first federal agency tasked with enforcing immigration laws because it had the most closely aligned mission, personnel, and office locations through its supervision of international trade.

Despite having gained the Chinese government’s agreement to its right to “restrict” Chinese immigration, in practice the United States interpreted the laws more aggressively than did the Chinese. As enforcement of the anti-Chinese laws reached for outright exclusion, the Chinese government steadily objected to the accumulation of legal discriminations afflicting Chinese as legally excluded persons. In the face of this opposition, the U.S. government nonetheless continued to assert and expand its authority over immigration and excludable immigrants in cases specifically involving Chinese [Chae Chan Ping 1889, Fong Yueting 1893, Wong Wing 1896]. By the 1910s, the United States was moving toward enacting immigration laws largely as a matter of domestic, sovereign authority. This standard of independent national-state authority over immigration was gaining acceptance around the world. Other international conventions developed concerning practices for the handling migrants including deported or excluded persons, extradition, visa processing and verification, and enforcement of entry restrictions.

Campaigns to limit immigration gained national urgency during the 1890s in response to rising levels of immigration comprised increasingly of southern and eastern Europeans, including more Jews and Catholics. Seeking to reduce these numbers and maintain a demographic balance closer to that of the early republic with its predominantly western and northern European Protestants, the United States enacted its strictest immigration laws in the 1920s. It imposed a system of quantitative caps allocated by national origins and banned altogether immigration from Asia. Following World War I, public support for such isolationism was propelled by many additional factors such as the moral decay of European civilization that the war had revealed and fears of spreading radicalism after the Russian Revolution. Overall immigration plummeted several-fold for several decades following. Improved enforcement procedures in which diplomatic offices abroad handled approval of visa and passport applications prevented millions of potential immigrants from even departing for U.S. shores. In contrast, no immigration limits were imposed on neighboring countries within the American hemisphere in order to maintain friendly relations, acknowledge the realities of trans-border communities, and facilitate long-standing economic partnerships.

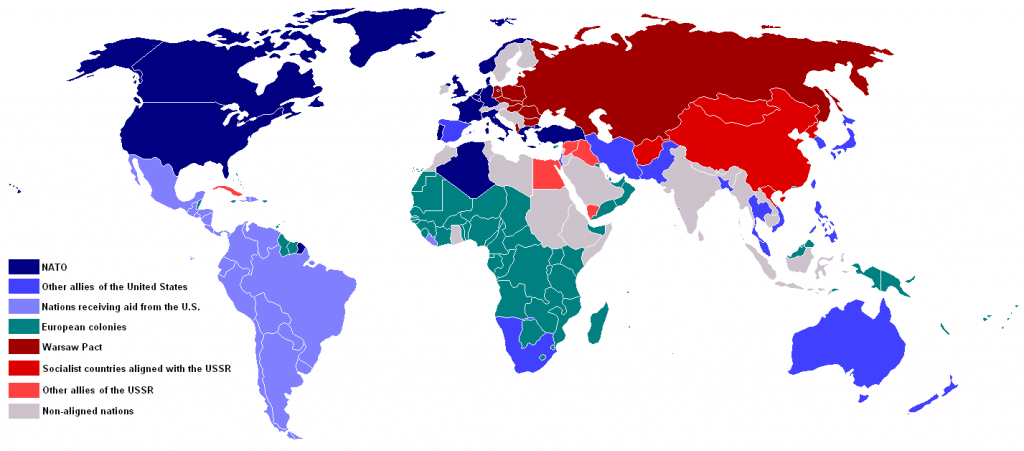

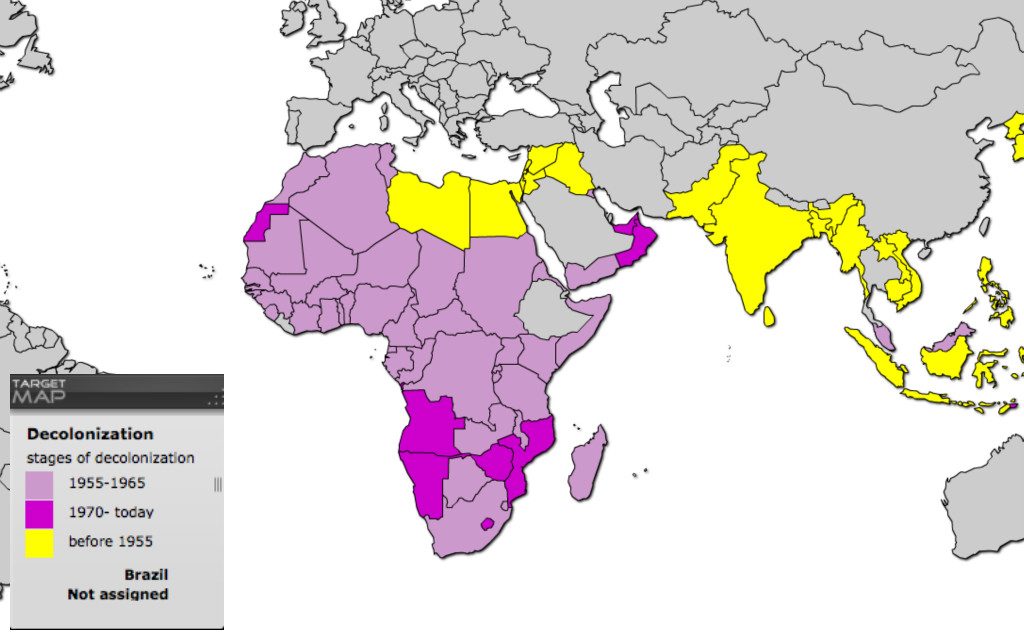

Not until World War II did the United States acknowledge international relations that applied pressures to liberalize immigration laws. The United States sought to exert global leadership which required the strengthening of political alliances, particularly with Asian nations that had previously had their immigration barred altogether. Immigration reforms started with the repeal of Chinese exclusion in 1943 and then immigration reforms affecting India and the Philippines [Luce Celler] in 1946. The Cold War required even broader reforms with many new nations in Asia, the Pacific, Caribbean, and Africa emerging from decolonization. The 1952 McCarran-Walter Act ended racial restrictions on citizenship and provided for each of these new countries to receive immigration quotas even as it maintained clear preferences for immigration from Europe.

World War II had resulted in the redrawing of many national boundaries, while the Cold War propelled the hardening of many political divides, particularly between the communist and democratic world systems. These divisions produced millions of displaced persons and refugees who required new homes. International conventions developed that authorized immigration and sanctuary provisions for refugees and asylum seekers. The United Nations passed the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the United Nations High Commission on Refugees issued standards in the 1951 Refugee Convention on Human Rights. Current international policies date to these documents and require consideration for all asylum seekers fleeing persecution so that they might gain sanctuary and not be forced to return to a place in which they face danger. See the teaching module on refugees and asylum seekers for more information.

The Cold War and the Civil Rights movement applied heavy pressures for the United States to find rationales for restricting immigration to replace offensive policies that prioritized race and national origins as the main criteria for admissibility. The pathway to more acceptable priorities in immigration restriction could be found even in its earliest, most discriminatory laws. As early as the 1882 anti-Chinese law, exemptions had been made for persons whose journeys were seen as beneficial or neutral in impact, such as diplomats, merchants and their families, tourists, and students. In particular, students from around the world found welcome in U.S. university and college campuses because international education programs were believed to spread the influence of the United States by inculcating the leaders of poorer and struggling societies to emulate U.S. civilization, progress, and values. In the first decades of the 1900s, the U.S. government even provided scholarships for elite Chinese (1909-29) and Filipino students (1903-10) to study in the United States with many graduates returning to their homelands to assume leading roles in government.

Immigration restrictions have always accommodated and protected international students. After World War II, international education and exchange programs became staple Department of State programs with funding authorized by the Smith-Mundt and Fulbright Acts. The numbers of international students coming to the United States has steadily increased, as did the realization that elite students from around the world with established educational credentials and training in practical fields were also promising candidates to become highly productive U.S. citizens.

The 1965 Hart-Celler Immigration Act incorporated these changing views of immigration and international relations by removing the offensive preferences based on race and national origins and providing permanent admissions for refugees, giving all countries the same immigration quotas, and prioritizing family reunification and employment and educational attainment. This law enabled dramatic increases in legal immigration from diverse parts of the world even as it generated new problems.

Unexpectedly, the imposition of the same quantitative limits on immigration from all countries produced intractable problems with the U.S.’s neighbors. Proximity and shared physical spaces fostered much higher levels of regular crossings and circular migrations for employment, family and friendships, business, and other aspects of daily life. The shortfall between the quantitative limits imposed by U.S. immigration policy and what had been local travel for regular daily life led to restricted border crossings that have produced a sizable population of unauthorized immigrants. The 1986 Immigration and Reform Control Act sought unsuccessfully to resolve this situation by granting amnesty to long-term residents with no criminal records while strengthening provisions for border controls and enforcement of employment restrictions. The 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act added further enforcement measures targeting employment and border control. Despite these efforts, unauthorized migrations have continued and constitute severe strains on U.S. relations to its poorer neighboring countries.

The twenty-first century witnessed dramatic expansion of immigration enforcement institutions. 9-11 inflamed concerns about national security related to immigration and border control, leading to the establishing of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in 2002 to consolidate and expand security and policing operations, including the rounding up, detention, and deportation of unauthorized immigrants. Relations with neighboring American nations have become straitened with the criminalization of migrant circulations that are continuations of historic flows of peoples traveling for economic, familial, and social purposes between interlocking areas. The changes in immigration enforcement have produced conditions by which about 11 million unauthorized immigrants reside in the United States. Although these unauthorized immigrants largely do not pose security risks they cannot attain legal status because they have violated U.S. immigration laws and are a permanent group of second-class citizens. The challenges they pose to the democratic ideals of the United States and its relations to its nearest neighbors highlight serious failings of current immigration policy and enforcement. Improved policies and practices would serve more effectively to identify and exclude threats to the United States, while protecting cooperative and benign migrations shared by the United States and its closest neighbors.

Lesson Plan

Introductory Activity:

Ask students what they notice about the chart. Are there any patterns they notice? (which regions/countries are missing-e.g. the Americas, which countries have the lowest numbers, which countries have the highest, etc.)

Reed’s rationale:

Do they agree with Reed? Why or why not? Why might Reed’s rationale be publicized?

Guided Practice

1. Post the laws and policies with their summaries around the classroom.

2. Students should have time to read through the historical events and examine the images: International Relations Handout

3. Students will look through the laws and policies posted around the classroom and match which immigration policies are connected to historical events:

(Related Law: 1803 Ban on Importation)

Extract of a letter from Charleston, dated November 21th:

“On Saturday last a plot was discovered, which may have saved some lives and some property. Seventeen French negroes intended to set fire to the town in different places, kill the whites, and probably take possession of the pow[d]er magazine and the arms; but luckily one of them turned states evidence. Five have been apprehended, two hung, and the others have escaped into the country.”

From the Charleston State Gazette of the 22d ultimo.

On Tuesday, the 14th inst. the Intendant received certain information of a Conspiracy of several French negroes to fire the city, and to act here as they had formerly done at S. Domingo [Haiti]—as the discovery did not implicate more than ten or fifteen persons, and as the information first given was not so complete as to charge all the ringleaders, the Intendant delayed taking any measures for their apprehension until the plan should be more matured, and their guilt more closely ascertained; but the plot having been communicated to persons, on whose secrecy the city magistrates could not depend, they found themselves obliged on Saturday last to apprehend a number of negroes, and among others the following, charged (together with another not yet taken) as the ring-leaders, viz.—Figaro, the property of Mr. Robinett; Jean Louis, the property of Mr. Langstaff; Figaro the younger, the property of Mr. Delaire; and Capelle. . . .

The Pennsylvania Gazette, December 13, 1797.

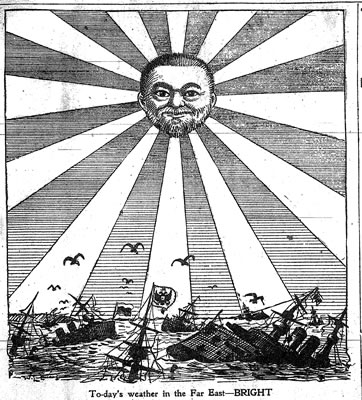

(Related Laws: Gentleman’s Agreement; Barred Zone Act)

Editorial Cartoons:

3. China and WWII:

(Related Laws: Luce Celler Act; Repeal of Chinese Exclusion)

4. Cold War & Decolonization

(Related Laws: McCarran Walter; Hart Celler; Parole Laws; Indochina Migration)

Conclusion:

Divide the class into four groups. Assign one historical event and the related immigration law(s) to each group. Students in each group will discuss and then write a brief summary outlining how they believe the event and the law(s) are related. Each group will share out to the class.

Chronology

Congress enacted deportation laws targeting persons deemed political threats to the United States in response to conflicts in Europe.

The Haitian revolution led Congress to ban immigration by free blacks to contain anti-slavery campaigners.

During the presidency of Andrew Jackson, this law authorized the confiscation of land from Native Americans and provided resources for their forced removal west of the Mississippi River.

In the settlement of the Mexican-American War, this treaty formalized the United States' annexation of a major portion of northern Mexico, El Norte, and conferred citizenship on Mexicans choosing to remain in the territory.

Negotiated during construction of the Transcontinental Railroad which relied heavily on Chinese labor, this international agreement secured US access to Chinese workers by guaranteeing rights of free migration to both Chinese and Americans.

This program sent about 120 Chinese students to study in New England and is often cited as a pioneering effort in mutually beneficial systems of international education which promoted the sharing of knowledge and understanding and improved international relations.

This treaty updated the 1868 Burlingame Treaty with China, allowing the United Stated to restrict the migration of certain categories of Chinese workers. It moved U.S. immigration policy closer to outright Chinese exclusion.

This law was a major shift in U.S. immigration policy toward growing restrictiveness. The law targeted Chinese immigrants for restriction-- the first such group identified by race and class for severely limited legal entry and ineligibility for citizenship.

The Supreme Court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment did not apply to Native Americans who did not automatically gain citizenship by birth and could therefore be denied the right to vote.

Complaints about the reservation system for Native Americans led Congress to authorize the president to allot – or separate into individual landholdings – tribal reservation lands. Native Americans receiving allotments could gain U.S. citizenship, but often lost their land.

Congress extended domestic authority over immigration to improve enforcement of the Chinese exclusion laws. It abolished one of the exempt statuses, returning laborers, stranding about 20,000 Chinese holding Certificates of Return outside the United States.

This law identified anarchists as targets for exclusion and made provision for their removal if detained after entry.

Congress extended the Chinese exclusion laws in perpetuity in response to the Chinese government's efforts to leverage better conditions for Chinese travelers to the United States by abrogating earlier treaties. Chinese communities organized an anti-American boycott in protest.

An international coalition of Chinese merchants and students coordinated boycotts of U.S. goods and services in China and some cities in Southeast Asia to protest the Chinese Exclusion laws.

Rather than enacting racially discriminatory and offensive immigration laws, President Theodore Roosevelt sought to avoid offending the rising world power of Japan through this negotiated agreement by which the Japanese government limited the immigration of its own citizens.

This act enacted U.S. citizenship for Puerto Ricans after the United States acquired the island as an incorporated territory in 1898.

This act gave the executive branch greater powers to enforce immigration restrictions during World War I. It particularly targeted anarchists and other potential radicals.

Fears of increased immigration after the end of World War I and the spread of radicalism propelled Congress to enact this "emergency" measure imposing drastic quantitative caps on immigration.

Immigration within the American hemisphere remained uncapped until 1965; however, in 1924 Congress authorized funding for the Border Patrol to regulate crossings occurring between immigration stations.

During the economic and political crises of the 1920s and 1930s, the Border Patrol launched several campaigns to detain Mexicans, including some U.S.-born citizens, and expel them across the border.

Completing the racial exclusion of Asians, Congress imposed immigration restrictions on Filipinos by granting the Philippines eventual independence. Previously, Filipinos could immigrate freely as U.S. nationals from a colony of the United States.

During World War II, the U.S. government negotiated with the Mexican government to recruit Mexican workers, all men and without their families, to work on short-term contracts on farms and in other war industries. After the war, the program continued in agriculture until 1964.

The importance of China as the U.S. government's chief ally in the Pacific war against Japan led Congress to repeal the Chinese Exclusion laws, placing China under the same immigration restrictions as European countries.

Congress enacted exceptions to the national origins quotas imposed by the Immigration Act of 1924 in order to help World War II soldiers and veterans bring back foreign spouses and fiances they had met while serving in the military.

Senator Fulbright of Arkansas proposed using proceeds from the sale of war surplus materials to fund programs to improve mutual understanding between the U.S. and the rest of the world through personnel exchanges and international education.

In contrast lawmakers' widespread indifference before World War II, after the war, under pressure from the White House and Department of State, Congress authorized admissions for refugees from Europe and permitted asylum seekers already in the U.S. to regularize their status.

This UN Refugee Convention set international standards for refugee rights and resettlement work. It is administered by the United Nations High Commission on Refugees. Wary of international obligations, President Truman refused to sign the U.S. government on to the convention.

The McCarran-Walter Act reformed some of the obvious discriminatory provisions in immigration law. While the law provided quotas for all nations and ended racial restrictions on citizenship, it expanded immigration enforcement and retained offensive national origins quotas.

Dissatisfaction with the 1952 McCarran-Walter Act inspired support for this legislation which provided 214,000 visas to refugees, primarily from Europe but with 5,000 designated for the Far East.

Even as the bracero program continued to recruit temporary workers from Mexico, the Immigration Bureau led round ups of Mexican nationals. The Bureau claimed to have deported one million Mexicans.

The Immigration Bureau and the FBI used this program to try regularize the statuses of the many Chinese Americans who had entered the United States using some form of immigration fraud under the discriminatory Chinese exclusion laws.

This law set the main principles for immigration regulation still enforced today. It applied a system of preferences for family reunification (75 percent), employment (20 percent), and refugees (5 percent) and for the first time capped immigration from the within Americas.

After Fidel Castro's revolution, anti-communist Cubans received preferential immigration conditions because they came from a historically close U.S. neighbor and ally. This law provided them permanent status and resources to help adjustment to life in the U.S.

The UNHCR issued this protocol in 1967 to implement the goals of the 1951 Refugee Convention, which set forth the key principle of refoulement, or that persons in flight from persecution and danger cannot be forced to return to places of danger.

The United States made provisions to admit about 135,000 Vietnamese and other Southeast Asians in the months following the fall of Saigon, resettle them across the United States with resources to help them establish new lives.

The Mariel boatlift refers to the mass movement of approximately 125,000 Cuban asylum seekers to the United States from April to October 1980. It prompted the creation of the Cuban-Haitian Entrant Program.

To address the problem of unauthorized immigration, Congress implemented through bipartisan agreement a multi-pronged system that provided amnesty for established residents, increased border enforcement, enhanced requirements of employers, and expanded guestworker visa programs.

Congress revised the Immigration Act of 1965 by implementing the H-1B visa program for skilled temporary workers, with some provisions for conversion to permanent status, and the diversity visa lottery for populations unable to enter through the preference system.

The regular denial of asylum applications from Salvadorans and Guatemalans fleeing violence in their homelands during the 1980s led to this legal challenge which forced changes to U.S. procedures for handling such cases.

Legislated in response to the brutal Chinese government crackdowns on student protests in Tiananmen in 1989, this law permitted Chinese students living in the United States to gain legal permanent status.

The Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act (NACARA) allowed certain Salvadorans, Guatemalans, and Nicaraguans who had fled violence and poverty in their homelands in the 1980s to file for asylum and remain in the United States.

Under the Haitian Refugee Immigration Fairness Act (HRIFA), enacted by Congress on Oct. 21, 1998, certain Haitian nationals who had been residing in the United States could become legal permanent residents.

The Homeland Security Act created the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) by consolidating 22 diverse agencies and bureaus. The creation of DHS reflected mounting anxieties about immigration in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11th.

Passed in October 2006, this law mandated that the Secretary of Homeland Security act quickly to achieve operational control over U.S. international land and maritime borders including an expansion of existing walls, fences, and surveillance.